“Hand Drum Wider” by lalunablanca via Flickr

By Tony Barnstone

Two years ago, I found myself at a music party at an apartment in Santa Monica. The party was being thrown to welcome a Sri Lankan drummer named Pabulu, who had come to California on a Fulbright scholarship, and I was invited because Pabulu was renting the spare bedroom of my then-girlfriend’s apartment. He was cheerfully Zen as any beachside stoner, but when he put his hands on his drum and pulled out those kinetic patternings—all rattlesnakes and castanets and Slinkys slinking down the stairs—wow! The rhythm made your bones start jumping in your skin like a skeleton on a string.

At the time, I had just published a book based upon 15 years of research into the Pacific theater of WWII, Tongue of War: From Pearl Harbor to Nagasaki (BkMk Press, 2009). In that book, I created dramatic monologues, largely in sonnet form, out of oral histories, histories, diaries, letters, memoirs, and my own interviews with vets and their families. It was a book that told stories of the Pacific theater of WWII not from the God’s eye view but from the earthly perspective of American and Japanese civilians and soldiers who lived and suffered through Pearl Harbor and Iwo Jima, the firebombing of Tokyo and the atom bomb drop on Hiroshima.

That night at the party, I was thinking about my desire to take the project further—to make it a graphic novel, perhaps, or a play, or better yet, a cycle of songs. I knew these were important stories, ones that needed to be in the world in a way that might attract a larger audience, and that the book alone wouldn’t do. It didn’t matter that my book had had success with prizes and fellowships. Books of poetry sell a thousand or few thousand copies. We live in a country of 314 million people. You can’t argue with math.

I was thinking about a boy I knew who used to get the word “musician” confused with “magician,” because we were settled on the circle of couches where a swart, Italianate fellow was declaiming about his past life as a semi-professional magician. He’d given up that life, but it was clear that coin and card tricks still came in handy to give his attempts at flirtation a bit of sorcery.

He’d gathered a little cluster of tattooed and lip-ringed women, and was playing the crowd for oohs and aahs and laughs—until he was interrupted, upstaged by the advent of the real magic. Pabulu sat down at his drum. Eliot set up a set of mics. And people began strumming, wailing, drumming, saxing, jazzing, riffing, dancing.

It was a fine concert, one great act after another, but the one who really wowed me was an independent singer-songwriter named John Clinebell, who performed an amazing set. I remember especially loving his powerful song, “The End,” a subtle sweet song that reminded me of early Simon and Garfunkel.

I came up, somewhat shyly, to congratulate him, and as we fell to talking I opened up about my idea for a CD of WWII music based on my poems. He looked at me and said, “You know, that’s something I might be interested in.”

From that one phrase emerged a whole Volkswagen of circus clowns. I spent the bulk of my savings and the next two years of learning how to write song lyrics, hire a producer, find a studio, arrange songs, hire studio musicians, create a promo video mix, master, print, and create a CD label and a music publishing company.

We were lucky to be joined in the project some months later by my other favorite L.A.-based indie singer-songwriter, Ariana Hall, who gave the Yin to John’s Yang and helped make this war CD speak to the experiences and sufferings of wives, and navy nurses, and “comfort women” who were forced to be sex slaves for the Japanese army.

Too often, when poets collaborate with musicians the music is meant to accessorize the poem—it’s the bling and not the dress, the parsley and not the steak, a moon orbiting around the poet’s Jupiterish ego. We decided from the beginning not to do a spoken word album with music in the background, but to make a true music CD, and to do that we knew we’d have to translate and adapt the poems to fit the new genre—just as a novel needs to be cut and condensed and rearranged to become a watchable screenplay.

Though the subject matter of the CD is often dark, and many of the songs deal with atrocity—sex slavery, torture, internment camps, even cannibalism—the CD itself is designed to be listenable and to balance joy and sorrow in its moods. Ethically, as well, the CD is meant to be balanced—taking a neutral stance and allowing each character to speak his or her views, without judgment, assuming that listeners will find their own moral paths through these competing voices and viewpoints. As one character says in Tongue of War, “Seems everyone has a point of view, but no one has perspective.”

Now, two years out from that party in Santa Monica and after far too many delays and a long production hell, I’ve sent a 15-song CD is off to the printer and in a few weeks we will have the finished product in our hands. This is as amazing to me as it would be if I could learn to pull a rabbit out of my nose, or transmute an elephant into mouse.

Now, two years out from that party in Santa Monica and after far too many delays and a long production hell, I’ve sent a 15-song CD is off to the printer and in a few weeks we will have the finished product in our hands. This is as amazing to me as it would be if I could learn to pull a rabbit out of my nose, or transmute an elephant into mouse.

After all, I am utterly ignorant as a music producer. And yet, somehow I lucked out and found terrific people to work with—Andrew Bush, our producer, donated countless hours of his time, and added percussion, guitar, mandolin, bouzouki, and piano to the album; Ruben Cohen mastered the album at Lurssen Mastering, where they have won several Grammys—notably for the terrific collaboration between Led Zeppelin’s former front man Robert Plant and bluegrass singer Allison Krauss (Album of the Year, 2009).

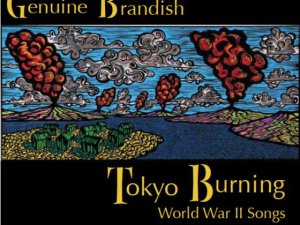

I’m ignorant, but I’m learning. The CD is called “Tokyo’s Burning,” and it will be available on CD Baby and Amazon.com and iTunes as soon as I figure out how to do that. I even have a Facebook page devoted to the album and a Twitter account I don’t tweet on often enough.

But this is not a story about what a lousy businessman I am. It’s a story about how I went from flirting with an idea to getting lucky, luckier than that guy on the couch, I’m guessing. It’s about how I confused lyric poetry with song lyrics and found that when you put the two of them together you get something that makes you sing to your windshield and your shower curtain. I think it’s a kind of magic.

Tony Barnstone is the Albert Upton Professor of English at Whittier College, author of twelve books (including four of poetry, five of translation from Chinese, and three world literature textbooks) and winner of the John Ciardi Prize, Benjamin Saltman Award, Pushcart Prize California Arts Council, NEA Fellowship, Poets Prize, and many others. Recent multimedia work includes a poetry graphic novel, a poetry deck of cards, and “Tokyo Burning,” a CD of original music.

Tony Barnstone is the Albert Upton Professor of English at Whittier College, author of twelve books (including four of poetry, five of translation from Chinese, and three world literature textbooks) and winner of the John Ciardi Prize, Benjamin Saltman Award, Pushcart Prize California Arts Council, NEA Fellowship, Poets Prize, and many others. Recent multimedia work includes a poetry graphic novel, a poetry deck of cards, and “Tokyo Burning,” a CD of original music.

Very cool – I like the promo video and look forward to the release of the CD. I especially love your mission of giving voice to individuals in history – it can be so easy to get lost in the vastness of war numbers. One of my favorite poetry workshops to teach is war poetry with 7th and 8th graders before their school trip to DC. Students write poems written as letters of address to individual soldiers buried at Arlington and then read them aloud during their visit to the cemetery. And two years from incpetion to distribution for the CD

– that’s inspirational!

Hi All,

Well, at long last the CD is out! It can be found at Amazon.com, Spotify, and CD Baby. Here’s a link: http://www.cdbaby.com/cd/genuinebrandish